ESSAYS > ESSAY: MARGARET McCANN

Catherine Kehoe’s Time Travel

By Margaret McCann

Painters have always drawn from precedents, through master to apprentice, and travels in Italy. The opening of public museums fostered Degas’s and Manet’s introduction before a Velazquez at the Louvre, and explains how Picasso encountered African art in Paris. Recently, the art world has moved far beyond Cold War limits, when the past was rejected in pursuit of novelty.

Cyberspace makes the study of various styles and skills readily available. As global cross-pollination encourages innovation, the past has returned as prologue. Catherine Kehoe’s “Back and Forth” reflects the time travel painters take between history and innovation, memory and presence, motif and canvas. The show comprises transcriptions of masterworks, studies of family photographs, and miscellany.

The More Things Change demonstrates painting’s reification of the past. As in the nostalgic early work of Martin Mull, the memory containers that are photographs offer as much mystery as history. Glimpses of likeness, posture, and micro-expression that photos capture convey a range of possible narratives. Appearing in profile, the group witnesses something off the right side of the picture we can’t see, like Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. They are as transfixed in the moment as they are locked into this compositional configuration, a blend of richly subdued color and blocky shape straddling representation and abstraction. While Kehoe’s relatives keep their distance on the other side of the table, a solidly defined foreground dish engages us, activating our proximal reaching impulse.

After Chardin addresses this close world at hand in more ways than one. In excluding “the world beyond the far edge of the table” — explains Norman Bryson in Looking at the Overlooked — still life positions the viewer as though seated before a tabletop, where bodily sensations associated with handling objects and forming them from clay are triggered.

To this dynamic Kehoe adds the arm’s action of layering paint in varying thicknesses, pressures, and speeds. The illusion of three dimensionality and the artifice of the painter’s handiwork are in tension. Forms follow Chardin’s carefully overlapping space, but the bulky shapes Kehoe casts them in hold differing weights on the picture plane; the cheese wheel is both near and far. Light follows Chardin’s elegant chiaroscuro, but invented texture replaces his softening atmosphere.

While Chardin’s casualness relaxes into ordinariness, removing the “distance between the viewer and what is seen,” writes Bryson, Kehoe’s formalist interpretation creates aesthetic remove.

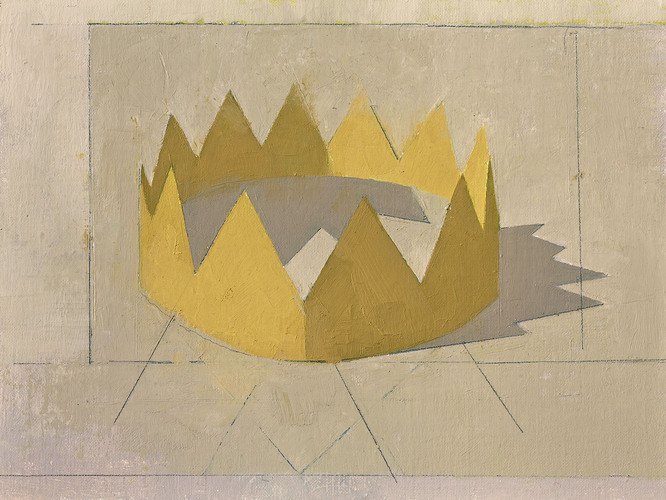

Kehoe elides the spatial calculations and decorative detail of Ruskin’s Perspective Study of a Crown in her Diadem after Ruskin. The corona bending into space becomes a string of triangular shapes in a nearly floating, flat pattern, engaging the simplicity of minimalism. Opaque color replaces Ruskin’s transparency, and violet shadows complement yellows in a muted arrangement reminiscent of Morandi. Crisp description and opaque paint recall that of Euan Uglow. Near the center, a saturated lavender advances to the picture plane. The personality of colored light that Impressionism highlighted is coordinated with the architectonics of Cubism. Ruskin lauded Turner’s devotion to natural phenomena, a legacy formative to Monet, who would then empower shadows to carry their own color agency, rather than to define plasticity. This avant-garde trajectory would fragment the order of light and shadow, conflate figure and ground, enliven the picture plane, and lead to the pure beauty of abstract painting. Thereafter, the painter’s task increasingly moved from documentation to invention.

Kehoe’s empirical eye also relishes investigating random subject matter. In Dior and Balenciaga, two hanging dresses offer exploration of the sculptured folds of tailored cloth, implicating the volumes of Edwin Dickinson and the gowns of de Hooch. Prevailing mid-tones make the white shape glow, while complementary greenish neutrals enrich the deep red form, its palette evoking Corot. Here, perception’s constant, point-to-point measuring poses an additional side-by-side comparison. While elements of the “male gaze” feminist Laura Mulvey explored are insinuated, the image also suggests a closet, store window, or dressing room mirror, and the title locates the viewer to a position of choosing. Vanity is incited, as is the whimsical function of a free-range analytical gaze, as the aesthetics of high fashion and the painting lexicon intersect.

In Don’t Be a Stranger an unvarnished visage is fleshed out by the palette knife. Daylight articulates facial planes from one side, while another window’s bold contrasts press in from the back wall. The head is tensely placed between it and the picture plane, somehow occupying the luminous interior. The viewer moves back and forth between accessibility and design, real and ideal, as though Kehoe conferred with both Monet and Mondrian. Guesswork encourages longer looking; how was equilibrium among the elements of proportion, perceptual tonality, invented color, flatness, form, and facture achieved? The painter’s inscrutable gaze, equally present and receding, gives nothing away.

Margaret McCann is a painter in New York City who writes for Two Coats of Paint and teaches at the Art Students League.

By Margaret McCann

Painters have always drawn from precedents, through master to apprentice, and travels in Italy. The opening of public museums fostered Degas’s and Manet’s introduction before a Velazquez at the Louvre, and explains how Picasso encountered African art in Paris. Recently, the art world has moved far beyond Cold War limits, when the past was rejected in pursuit of novelty.

Cyberspace makes the study of various styles and skills readily available. As global cross-pollination encourages innovation, the past has returned as prologue. Catherine Kehoe’s “Back and Forth” reflects the time travel painters take between history and innovation, memory and presence, motif and canvas. The show comprises transcriptions of masterworks, studies of family photographs, and miscellany.

The More Things Change demonstrates painting’s reification of the past. As in the nostalgic early work of Martin Mull, the memory containers that are photographs offer as much mystery as history. Glimpses of likeness, posture, and micro-expression that photos capture convey a range of possible narratives. Appearing in profile, the group witnesses something off the right side of the picture we can’t see, like Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. They are as transfixed in the moment as they are locked into this compositional configuration, a blend of richly subdued color and blocky shape straddling representation and abstraction. While Kehoe’s relatives keep their distance on the other side of the table, a solidly defined foreground dish engages us, activating our proximal reaching impulse.

After Chardin addresses this close world at hand in more ways than one. In excluding “the world beyond the far edge of the table” — explains Norman Bryson in Looking at the Overlooked — still life positions the viewer as though seated before a tabletop, where bodily sensations associated with handling objects and forming them from clay are triggered.

To this dynamic Kehoe adds the arm’s action of layering paint in varying thicknesses, pressures, and speeds. The illusion of three dimensionality and the artifice of the painter’s handiwork are in tension. Forms follow Chardin’s carefully overlapping space, but the bulky shapes Kehoe casts them in hold differing weights on the picture plane; the cheese wheel is both near and far. Light follows Chardin’s elegant chiaroscuro, but invented texture replaces his softening atmosphere.

While Chardin’s casualness relaxes into ordinariness, removing the “distance between the viewer and what is seen,” writes Bryson, Kehoe’s formalist interpretation creates aesthetic remove.

Kehoe elides the spatial calculations and decorative detail of Ruskin’s Perspective Study of a Crown in her Diadem after Ruskin. The corona bending into space becomes a string of triangular shapes in a nearly floating, flat pattern, engaging the simplicity of minimalism. Opaque color replaces Ruskin’s transparency, and violet shadows complement yellows in a muted arrangement reminiscent of Morandi. Crisp description and opaque paint recall that of Euan Uglow. Near the center, a saturated lavender advances to the picture plane. The personality of colored light that Impressionism highlighted is coordinated with the architectonics of Cubism. Ruskin lauded Turner’s devotion to natural phenomena, a legacy formative to Monet, who would then empower shadows to carry their own color agency, rather than to define plasticity. This avant-garde trajectory would fragment the order of light and shadow, conflate figure and ground, enliven the picture plane, and lead to the pure beauty of abstract painting. Thereafter, the painter’s task increasingly moved from documentation to invention.

Kehoe’s empirical eye also relishes investigating random subject matter. In Dior and Balenciaga, two hanging dresses offer exploration of the sculptured folds of tailored cloth, implicating the volumes of Edwin Dickinson and the gowns of de Hooch. Prevailing mid-tones make the white shape glow, while complementary greenish neutrals enrich the deep red form, its palette evoking Corot. Here, perception’s constant, point-to-point measuring poses an additional side-by-side comparison. While elements of the “male gaze” feminist Laura Mulvey explored are insinuated, the image also suggests a closet, store window, or dressing room mirror, and the title locates the viewer to a position of choosing. Vanity is incited, as is the whimsical function of a free-range analytical gaze, as the aesthetics of high fashion and the painting lexicon intersect.

In Don’t Be a Stranger an unvarnished visage is fleshed out by the palette knife. Daylight articulates facial planes from one side, while another window’s bold contrasts press in from the back wall. The head is tensely placed between it and the picture plane, somehow occupying the luminous interior. The viewer moves back and forth between accessibility and design, real and ideal, as though Kehoe conferred with both Monet and Mondrian. Guesswork encourages longer looking; how was equilibrium among the elements of proportion, perceptual tonality, invented color, flatness, form, and facture achieved? The painter’s inscrutable gaze, equally present and receding, gives nothing away.

Margaret McCann is a painter in New York City who writes for Two Coats of Paint and teaches at the Art Students League.