ESSAYS > ESSAY: JOHN YAU 2

THE PAINTINGS OF CATHERINE KEHOE

By John Yau

The opening sentences of John Ashbery’s “New Spirit,” the first section of his book Three Poems (1972), which was written in dense, meditative prose, came to mind when I was thinking about the paintings that Catherine Kehoe has included in her exhibition, Before and After:

I thought that if I could put it all down, that would be one way. And next the thought came to me that to leave all out would be another, and truer way.

The two poles – inclusion and omission – define the boundaries within which Kehoe approaches her oil paintings on panel, few of which are larger than 10 by 8 inches. Within these boundaries, I would add the dialogue between abstraction and representation, and the one between the solidity of forms and the ethereality of light. Taken together, these oppositions and dialogues underscore the domain of perception explored by Kehoe through the medium of paint.

Working from observation, photos, and the invigorating experience of paintings by artists as varied as Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825), the first professional American painter of still life; the Flemish Baroque artist, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640); and the Dutch genre painter, Gerard ter Borch (1617-1681), Kehoe has established a number of motifs — the self-portrait, the portrait, the still life, interiors, and the work of other artists — she has revisited over the course of her career.

The palette of her intimately scaled paintings runs from subtle tonal shifts to sharp contrasts, while the palpable planes of paint look as if they have been applied with a palette knife. However, this is not the case; Kehoe in fact builds her paintings up with sable brushes. It is a slow process of accretion in which the materiality of paint is integral to the work.

In the paintings chosen for Before and After — beginning with SP (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000) and culminating in After Rubens (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2020) — there is a strong emphasis on how women see themselves, how they have been seen in art, and how they have played important roles in the lives of artists.

In the still lifes, Kehoe returns to objects she has depicted in earlier paintings, always seeing them with fresh eyes.

In Alabaster Dish (oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches, 2020), a pale green stemmed dish rises from a cubistic configuration of bright salmon rectangles, surrounded by a semi-abstract aura of gray shapes that could be wrapping paper or a shopping bag. Paradoxically, these flat, geometric shapes combine to carve out a palpably open space, a kind of abstract blossom ready to swallow up the dish.

The tension between the opalescent green tones of the alabaster and the faint reflection of the salmon-colored planes on the underside of the dish is one of the painting’s many quiet pleasures.

Another is the tonal shift between the outside of the dish and the four subtly pigmented orbs it contains. In this, the viewer encounters Kehoe’s focus on nuance, as she teases the slightest variations out of the medium of paint. Alabaster Dish evokes an entire world, at once sensual and reserved, permeated by light and shadow and, most of all, silence. Although the painting is intimately scaled, Kehoe has managed to open a space that contradicts its actual size.

In two portraits of the same woman, Muriel (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000) and MWK (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000), Kehoe depicts her white-haired subject in profile, facing right in Muriel and left in MWK. In both paintings, the woman is a wearing the same densely colored blue blouse.

In Muriel, the layered ground is a dark brown over green. The blue shirt, the fluffy, snowy-white hair with dabs of pink peeking through, and the face, which is made up of orange-brown planes, build up to a portrait of a women swimming in her own thoughts. We cannot see her eyes, as she is slightly turned away.

In MWK, the woman’s cheek is parallel to the picture plane and closer to the viewer than the face in Muriel. She is looking straight ahead, the side of her face a patchwork of slightly differing orange-brown tones.

We instantly recognize that it is the same person, but each painting – despite the compositional similarities and shared coloration – feels distinct. In MWK, my attention shifts from the evocations of flesh in the rectangles of paint to the subtle facial expression of a woman radiating a self-contained authority — a sense of composure that feels contiguous with Kehoe’s entire project. This differs markedly from the more unsettled emotions conveyed by the umber ground of Muriel, with its deflected gaze and dramatic shift between light and dark.

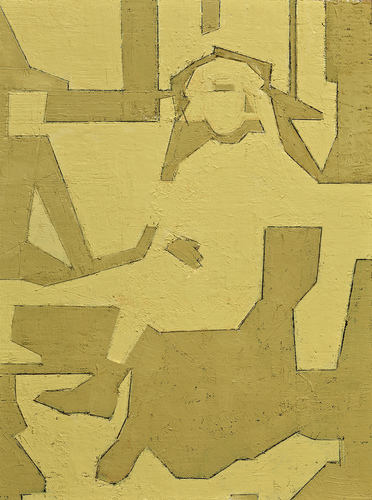

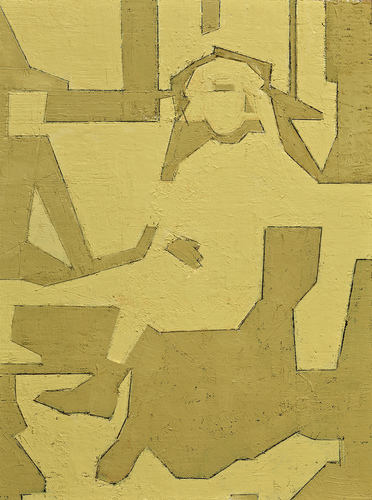

In contrast to the paintings I have just described – all of which are about the accretion of stroke, color, and texture – in Helen First Holy Communion (oil on panel, 7 x 5 inches, 2020) and Cyclamen (oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches, 2020), Kehoe finds different ways to leave things out, with each absence contributing to the painting’s meaning.

In Helen First Holy Communion, Kehoe uses two related but contrasting hues, beige and hazelnut tan, to paint interlocking shapes evoking the silhouette of a seated girl, her head covered in a veil. Unlike a photograph, which freezes an instant from the past, Helen First Communion, which was based on a photo, underscores our distance from the past, a sense of time lost and irrecoverable. We cannot clearly see the young communicant, though we feel she is there, inseparable from the paint.

Cyclamen is a color as well as the flower that the color is named after. In Kehoe’s painting, Cyclamen, we see not the expected deep purplish pink blossoms, but two white floral silhouettes set against a blue ground. If the artist had painted the flower petals in detail, they might not have stood out as sharply against the blue ground. Kehoe understands when to step back and allow shape alone to suggest a subject.

By opening herself up to the implications of her imagery, and refusing to settle into a single style, Kehoe empowers the painting to pull her along an unexpected trajectory. Full of nuance, distinctive hues, contrasting tones, and an exquisite sensitivity to light and shadow, her paintings are concentrated acts of looking.

John Yau is a poet and critic whose forthcoming books include a collection of poems, Genghis Chan on Drums (Omnidawn, 2021) and the first monograph on Liu Xiaodong (Lund Humphries, 2021).

By John Yau

The opening sentences of John Ashbery’s “New Spirit,” the first section of his book Three Poems (1972), which was written in dense, meditative prose, came to mind when I was thinking about the paintings that Catherine Kehoe has included in her exhibition, Before and After:

I thought that if I could put it all down, that would be one way. And next the thought came to me that to leave all out would be another, and truer way.

The two poles – inclusion and omission – define the boundaries within which Kehoe approaches her oil paintings on panel, few of which are larger than 10 by 8 inches. Within these boundaries, I would add the dialogue between abstraction and representation, and the one between the solidity of forms and the ethereality of light. Taken together, these oppositions and dialogues underscore the domain of perception explored by Kehoe through the medium of paint.

Working from observation, photos, and the invigorating experience of paintings by artists as varied as Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825), the first professional American painter of still life; the Flemish Baroque artist, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640); and the Dutch genre painter, Gerard ter Borch (1617-1681), Kehoe has established a number of motifs — the self-portrait, the portrait, the still life, interiors, and the work of other artists — she has revisited over the course of her career.

The palette of her intimately scaled paintings runs from subtle tonal shifts to sharp contrasts, while the palpable planes of paint look as if they have been applied with a palette knife. However, this is not the case; Kehoe in fact builds her paintings up with sable brushes. It is a slow process of accretion in which the materiality of paint is integral to the work.

In the paintings chosen for Before and After — beginning with SP (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000) and culminating in After Rubens (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2020) — there is a strong emphasis on how women see themselves, how they have been seen in art, and how they have played important roles in the lives of artists.

In the still lifes, Kehoe returns to objects she has depicted in earlier paintings, always seeing them with fresh eyes.

In Alabaster Dish (oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches, 2020), a pale green stemmed dish rises from a cubistic configuration of bright salmon rectangles, surrounded by a semi-abstract aura of gray shapes that could be wrapping paper or a shopping bag. Paradoxically, these flat, geometric shapes combine to carve out a palpably open space, a kind of abstract blossom ready to swallow up the dish.

The tension between the opalescent green tones of the alabaster and the faint reflection of the salmon-colored planes on the underside of the dish is one of the painting’s many quiet pleasures.

Another is the tonal shift between the outside of the dish and the four subtly pigmented orbs it contains. In this, the viewer encounters Kehoe’s focus on nuance, as she teases the slightest variations out of the medium of paint. Alabaster Dish evokes an entire world, at once sensual and reserved, permeated by light and shadow and, most of all, silence. Although the painting is intimately scaled, Kehoe has managed to open a space that contradicts its actual size.

In two portraits of the same woman, Muriel (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000) and MWK (oil on panel, 6 x 6 inches, 2000), Kehoe depicts her white-haired subject in profile, facing right in Muriel and left in MWK. In both paintings, the woman is a wearing the same densely colored blue blouse.

In Muriel, the layered ground is a dark brown over green. The blue shirt, the fluffy, snowy-white hair with dabs of pink peeking through, and the face, which is made up of orange-brown planes, build up to a portrait of a women swimming in her own thoughts. We cannot see her eyes, as she is slightly turned away.

In MWK, the woman’s cheek is parallel to the picture plane and closer to the viewer than the face in Muriel. She is looking straight ahead, the side of her face a patchwork of slightly differing orange-brown tones.

We instantly recognize that it is the same person, but each painting – despite the compositional similarities and shared coloration – feels distinct. In MWK, my attention shifts from the evocations of flesh in the rectangles of paint to the subtle facial expression of a woman radiating a self-contained authority — a sense of composure that feels contiguous with Kehoe’s entire project. This differs markedly from the more unsettled emotions conveyed by the umber ground of Muriel, with its deflected gaze and dramatic shift between light and dark.

In contrast to the paintings I have just described – all of which are about the accretion of stroke, color, and texture – in Helen First Holy Communion (oil on panel, 7 x 5 inches, 2020) and Cyclamen (oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches, 2020), Kehoe finds different ways to leave things out, with each absence contributing to the painting’s meaning.

In Helen First Holy Communion, Kehoe uses two related but contrasting hues, beige and hazelnut tan, to paint interlocking shapes evoking the silhouette of a seated girl, her head covered in a veil. Unlike a photograph, which freezes an instant from the past, Helen First Communion, which was based on a photo, underscores our distance from the past, a sense of time lost and irrecoverable. We cannot clearly see the young communicant, though we feel she is there, inseparable from the paint.

Cyclamen is a color as well as the flower that the color is named after. In Kehoe’s painting, Cyclamen, we see not the expected deep purplish pink blossoms, but two white floral silhouettes set against a blue ground. If the artist had painted the flower petals in detail, they might not have stood out as sharply against the blue ground. Kehoe understands when to step back and allow shape alone to suggest a subject.

By opening herself up to the implications of her imagery, and refusing to settle into a single style, Kehoe empowers the painting to pull her along an unexpected trajectory. Full of nuance, distinctive hues, contrasting tones, and an exquisite sensitivity to light and shadow, her paintings are concentrated acts of looking.

John Yau is a poet and critic whose forthcoming books include a collection of poems, Genghis Chan on Drums (Omnidawn, 2021) and the first monograph on Liu Xiaodong (Lund Humphries, 2021).